Trigger warning: This story recounts the experience of the death of a parent.

As my sisters reminded me this morning, today would have been my dad’s 70th birthday. He died more than 10 years ago, when he was 59 years old. This was the first, and one of the worst, tragic events of my life. In those 10 years, I have never felt ready to purposely think through and process the events of his death, and the impact it has had on my life since then. Even thinking about it now makes my heart race. I feel nervous to go back there. However, this date, and my recent commitment to processing through writing, comes to me as a challenge… a call to finally give myself a squeeze, know that I am now, more than ever, equipped to deal with this, and to take a look.

If you haven’t experienced grief, it can sometimes feel like an object on fire – too hot to touch, and too bright to look at. My mom’s death, which happened only 3 years ago, still feels molten, like glowing metal freshly pulled out of the forge. When it comes into my field of vision, I still get the urge to look away, or at least to only peer at it out of the corner of my eye. But with my dad, it’s been 10 years. It feels more like the embers of a huge fire, where it looks like it’s put out on the surface, but when you dig down, you find that there are still glowing coals underneath.

In my house in South Dakota, I had a fireplace insert, and would use it to heat the home through the winter with wood. On cold nights, we’d set a lot of wood inside, with the hopes that by the end of the night, the right amount of ash would have built up on top of the remnants of wood so that it would slow their burn. Those coals would be insulated enough to retain the high heat needed for ignition, but starved of just enough oxygen to slow their smoulder. In the early morning when I would wake up, if we were lucky, I’d find a pile of what looked like ash, but dig around underneath to find coals still hot enough to reignite once they got an infusion of oxygen and new wood on top.

Thinking back on my grief over the loss of my dad, I’ve done something similar these past 10 years. I’ve let other things pile on top, insulating the embers just enough to let them retain their slow burn, but never giving them enough oxygen to flare up and burn out. In treating it this way, I’ve held onto the grief, preserving it in a state where it’s almost always ready to burn up again if given enough oxygen.

Buried coals can be dangerous. Responsible campers know that you cannot fully tell if the fire is out by just feeling whether heat is rising off the top, and will douse water on the remnants to ensure it is extinguished. If hot coals are buried underneath, and wind blows ashes off of the top, exposing the coals to oxygen in the process, a fire can easily reignite. Grief can work the same way. You pile things on top, get busy and forget they’re there. But at some point, either life settles down, or you purposely start decluttering the things you’ve piled on top, and whether you’re ready or not, the fire needs to be tended again.

So what parts of my grief over my dad have remained “hottest”? I think back to the moment I found out. I had just gotten out of class at University of Miami – Practical Computing for Biologists – and looked at my phone and noticed many missed calls from my sister. (I didn’t yet have the anxiety that I now feel when I get multiple phone calls from family members). I don’t remember how the conversation started, but I remember it included,

“Where are you right now?”

“What are you doing?”

“Dad had a heart attack.” and

“Meg, he’s gone”.

And the finality of those last words. And dropping to the ground and just… wailing. The feeling of falling with no control and nothing to grab onto. And frantically searching my brain for the path that proved what she said to be wrong. And the instant knowledge of something bigger than us. Being like a baby in a crib with no way to reach something on a high shelf – seeing it and knowing it’s there, with no way to control the outcome. And the feeling that every second that passed was a second further from him being alive.

After what may have been 2 or 20 minutes on the phone, on the ground, wailing, with my sister on the other end, she told me I needed to get someone to drive me and to get to Nancy’s, where Dad still was. And stumbling up the stairs to the classroom I just left, flinging open the door, and sobbing, “I need a ride. I need someone to drive me”… then choking out, “My dad just died”. And the horrified look on my professor’s face, and the stunned silence in the room. After what felt like a very long pause, a classmate finally jumped up and said, “I can, let’s go.” (Thank you, Tara, for this kindness on a terrible day).

These images are seared into my mind, and may be there forever.

And the rest is a blur. I have very little recollection of the 30 minute drive north, but thinking about it now, it must have been almost as horrible for Tara as it was for me. I don’t remember walking in, but I remember hugging Nancy, her sons, and everyone telling me that if I wanted to see him, I needed to prepare myself to go into the room where he died, where he was still in bed. I remember the boys supporting me on either side as we walked into the room, and I saw him lying there, and feeling all strength leave my body as they held me up. He was lying in bed, and looked to be still asleep.

I have no clue what the value of going in to see him like that was. That is not to say that there was, or wasn’t a value to it. Maybe it helped me to face and accept the reality of the situation, that my dad was just… no longer alive.

His death was entirely unexpected. (As unexpected as it can be, knowing that at some point, it will come for all of us). I was 26 at the time, and had, 3 weeks prior, moved out after a year of living with him and Nancy in Miami. I was attending graduate school at University of Miami, studying marine biology, and living an absolute dream of a mid-twenties life. I was scuba diving every day, living close to amazing friends, making music daily as a member of a thriving Miami band, and had just moved into an iconic, magical Coconut Grove home.

Things were not perfect… despite the amazing daily tasks, there was some real negativity at my job and I did not have the tools to handle it in ways I might have been able to today. I had very little relationship with my mom, who was deeply struggling with alcoholism and in and out of rehab. (Both of those things are topics for another day). But despite that, I was deeply embedded into the world around me and feeling, experiencing, and learning a huge number of amazing things.

Before his death, I had begun feeling an incredible satisfaction and closeness one may experience with a parent when, as a young adult, you find that you share some of the same hobbies and interests with them. And sometimes you even get to give back — to share, teach, or guide them in return. A few months before his death, I had the epitome of this experience captured in one perfect day.

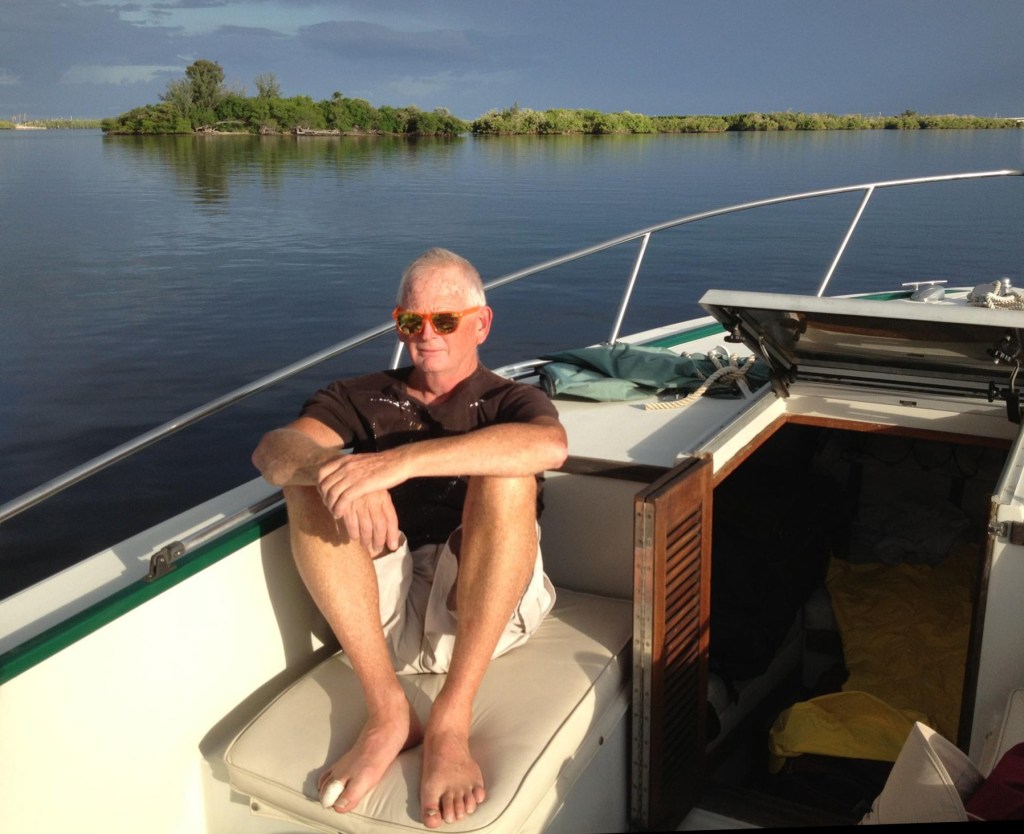

In pursuit of my master’s degree, I had gained many field skills—I was a certified boat operator for the National Park Service, skilled at navigating the tricky shallows of Biscayne Bay, and doing all sorts of interesting work both above and below the water. One day, he was able to join me as a park volunteer.

We set out, and I captained the boat across Biscayne Bay to conduct snorkel surveys and other park work along the mangrove keys. The weather was comfortable, the water was glassy, and I had the distinct sensation that time had stopped. For a moment, it felt like we were not just parent and child with histories and imperfections and dynamics, but just two people sitting in awe of our good fortune to be there, respect for each other, and acknowledgement of the rareness and meaning of the moment. I remember feeling and thinking, today is perfect.

Ten years later, I still return to this day. It provides calm and strength, and reminds me that despite the pain of his loss, I carry with me a collection of beautiful moments and memories. And those types of fires are always worth tending.

Leave a comment